It’s around half ten on a Tuesday morning, and Declan is in a pair of shorts and a tee shirt wandering around the kitchen. For the first time in twenty odd years, he has nowhere to go. There is no morning meeting or crisis to manage. His wife Grainne had left for work a couple of hours earlier, leaving him but not wanting to ask him how he was going to fill his day. This had been the routine for the past month since his role as Operations Director had been eliminated in a global re-organisation.

Declan stood in his silent kitchen, holding a cup of coffee, staring at the empty day ahead. “Who am I if I’m not the Operations man?” he thought. “What do I do with myself when there’s nothing I have to do?”

For 54-year-old Declan, this moment in his life represented more than job loss. It was the collapse of an identity he’d spent decades building. The title, the authority, the sense of purpose that came with leading a 250-person function was all gone. He was now a man who genuinely didn’t know what to do with unstructured time or silence. The silence and stillness played heavily on his mind. The sense of worthlessness was growing.

If you’re over 50, research shows you have a 50/50 chance that the decision to leave will not be within your control. For many senior executives, the loss of professional identity creates a psychological crisis that isn’t just about ego or status, it’s about the fundamental question of self-worth and purpose when the role that has defined you for decades suddenly disappears.

In this article, we’ll share Declan’s journey through an identity crisis.

*All names have been changed to protect the identity of the people involved in this personal and challenging executive transition.

Reality: When Work Becomes Who You Are

Senior roles demand extraordinary time, energy, and emotional investment. This creates an all-consuming professional identity that often crowds out other elements of self-identity that remain underdeveloped. We have identified five common identity-related challenges caused by executive job loss:

- Total Professional Immersion: Senior executives often work 60–80-hour weeks and remain accessible for urgent issues during personal time. This intensity creates a lifestyle where work thoughts, work relationships, and work challenges dominate mental and emotional space, leaving less time to truly switch on to the needs of family and those closest.

- Social Network Concentration: Social circles often focus on work relationships. Business dinners, industry events, and colleague friendships create social lives that are fundamentally professional. When the executive role disappears, much of the social structure that supported your personal identity disappears as well.

- Purpose and Meaning Dependency: Many executives derive deep personal satisfaction from leading teams, making strategic decisions and driving business results. This creates a sense of purpose and meaning that are enormously fulfilling. When this source of purpose is gone, it leaves a vacuum in their self-worth.

- Structure and Routine Loss: Busy roles provide intense daily structure—meetings, deadlines and decision points that create rhythm and purpose for each day. Without this externally imposed structure, many struggle with the complete freedom and lack of direction that characterizes time off between roles.

- Status Adjustment: Senior roles provide recognition and social status that become integrated into your self-perception. The shift from being sought out for opinions and decisions to being someone on the outside looking for new opportunities is psychologically bruising.

Declan’s Story: From Company Man to Lost Soul

Declan’s twenty-three career journey had seen him work his way up the organization from Process Engineer to Operations Director. His sense of daily purpose came from solving the constant challenges and his identity was completely intertwined with his employer. His social life revolved around company events and industry functions. He knew more people in the global organization than he did in his local community.

When the reorganization happened, roles were restructured within weeks. Declan went through a series of meetings and reached a negotiated settlement which offered a generous severance package with outplacement coaching to support his career transition.

As Declan explained: “One day I am making dozens of decisions that affected people’s livelihoods. The next day, I’m wandering around my kitchen with nothing to do and no one depending on me for anything!”

The first couple of weeks felt like a holiday. Declan caught up on projects around the house and in the garden and even enjoyed cooking for the family, something to be doing with his unstructured time. But by the end of the second week, the reality of his situation began to sink in.

“I didn’t know what to do with myself,” he recalls. “For twenty odd years, every morning I woke up knowing exactly what needed to be done. There were always problems to solve, people to meet, decisions to make. Suddenly, there was nothing. I could do whatever I wanted, yet I had no idea what that was and this really got into my head. It sounds ridiculous, but I’d built my entire adult life around external demands and suddenly there weren’t any!”

The identity crisis deepened. His wife Grainne was watching her previously decisive and confident husband asking her what she thought he should do with his day! It was like he’d lost all capacity for independent decision-making.

Social isolation compounded his identity crisis. Declan’s ‘always-on’ life revolved around work relationships and scheduled meetings. The phone was silent, no one wanted him to urgently solve a problem. Who was he now without his previous job title?

Declan explains: “I would bump into people, and they would ask what I was doing now, and I didn’t have a solid answer. I would end up stumbling through a sort of explanation. I was no longer the successful, busy, confident ‘Ops Guy’. I was now avoiding the supermarket or the local pub for fear of meeting people.” This lack of a current professional identity filled Declan with shame.

The Vulnerability: Trusting the Process

He had been offered outplacement support on leaving his employer but felt too ashamed to engage. He believed he could do this on his own. In hindsight, “I was reluctant to show the vulnerability that would come with opening up to anyone about my situation.” After six weeks of growing depression and social withdrawal, Grainne insisted that Declan take up the outplacement support and give it a try.

While initially resistant to the outplacement support, Declan agreed to meet to discuss how it could help. “To be honest, I just wanted help finding another role,” he admitted afterwards. “I didn’t realize I needed to do deeper work on myself to rebuild my confidence to be able to tell my story.”

As his outplacement coaching sessions progressed, it was clear Declan needed support with this identity transition. “Declan was clearly an accomplished leader with excellent capabilities, but his entire sense of self was tied to his executive role. He still spoke in the present tense when he described what he did in his Ops role previously. He couldn’t effectively pursue new opportunities until he understood his own value beyond that specific context.”

Our coaching work focused on identity archaeology. This focused on helping Declan rediscover aspects of himself that had been overshadowed by his executive role but remained core to who he is as a person.

“My coach made me realize that I’d become a person who only existed in relation to work,” Declan reflected. “She helped me understand that there was a Declan who existed before I became the Ops Guy, and this identity wasn’t dependent on an executive job title.”

The identity transition process began with structured reflection on Declan’s core values, intrinsic interests, and sources of personal satisfaction that existed independently of professional achievement.

The transition coaching guided him through exercises that explored his relationship with family, community involvement, personal interests, and the types of activities that provided satisfaction beyond work accomplishment.

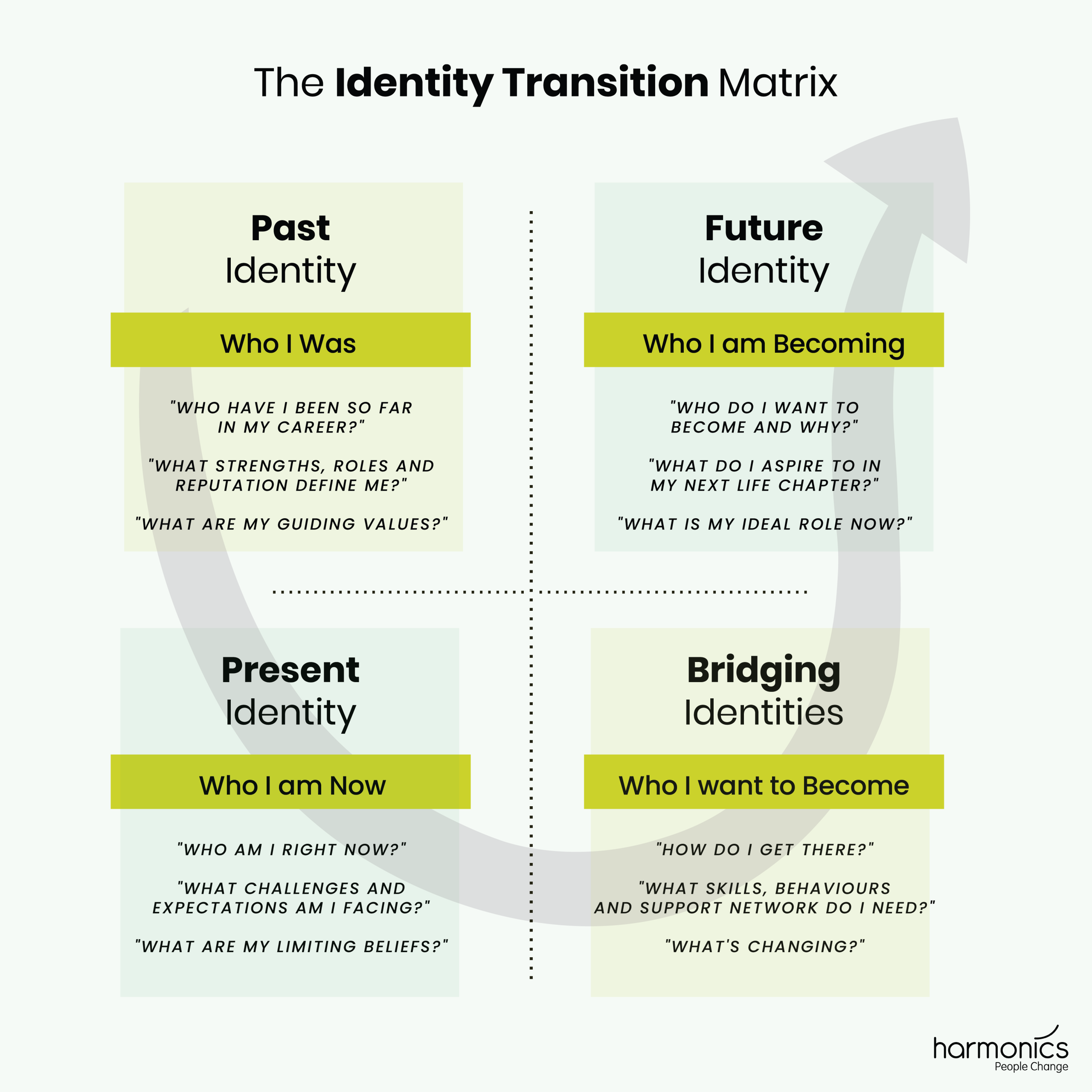

The four stage ‘Identity Transition Model’ below helped him reflect on his Past Identity – ‘the Ops Guy’ and what made him successful. The work on Present Identity helped him to share his current transition story in a more authentic and targeted way to others. The Bridging Identities work focused on researching and experimenting with future potential options. This helped him to narrow his focus on his ideal next role – his Future Identity.

Declan recalls: “One breakthrough came when my coach was probing me on times when I felt energized previously in work scenarios. I realized what I really loved was solving big problems, seeing people develop, and building something meaningful. I hadn’t lost those capabilities; I had lost my job and I just needed a new environment to bring these to life again; the challenge was I wanted it now, I wanted an instant solution!”

The Coming Out: Telling his Story

The practical identity work helped him to embrace this ‘gap in his career’ as a time to reaffirm his intrinsic values and life story to date and future ambitions. This created the shift from shame to pride. When Declan completed a personal story exercise, it helped him frame his identity story in three brief chapters:

- Essence – What were the early influences that shaped his life journey

- Experiences – What were personal qualities he derived from his life and career experiences

- Effect – What was the legacy he would like to leave the world.

This reaffirmed his authentic personal identity. He then used three slides to present his life and career journey to his coach. The coach could see the visible energetic transformation: “His body language totally changed as he brought his life journey to life, the emotion and passion in his voice were clear to hear and sense.”

Declan shared how this made him feel: “The Essence element of the exercise brought me back to my humble beginnings in life, it brought to life for me how my parents’ values and work ethic shaped my identity so powerfully. I had rediscovered my mojo and the fire within me.”

Soon after, Declan bumped into a close friend (also the local school principal) and started to share the impact of completing his own personal story exercise in the coaching. The principal jumped on the opportunity to get Declan to share his story with his transition year class. Declan shares: “Firstly, I was stunned to be asked and secondly, I realized the privileged position I found myself in; I could influence teenagers about life, career, success and failure. I went straight back to my own childhood in my head and how I would have loved this direction at that age. I felt I had meaning again.”

The talk became a springboard for speaking in other schools in the region. Declan was coming out again, this time with a deeper sense of identity and clarity on who he was and what he wanted. He was asked to join the Board of a Not-for-Profit Charity close to his heart after meeting with the Board Chair and asking some great questions which the Board hadn’t previously considered. He joined a local cycling group after a random conversation in a coffee shop led to an invite to try it out once. He decided to start his own professional development journey in Corporate Governance where he got to meet people from all industry sectors, including the person who would refer him to his new future employer.

Declan demonstrated three attributes observed in successful executive transitions: curiosity, creativity and clarity.

- Curiosity – asking questions and being vulnerable to not knowing the answer.

- Creativity – thinking about new ways to solve problems faced by Organizations today.

- Clarity – knowing what you would want in your future career and why.

The Transition: Research and Reconnection

His Outplacement coach had prompted him to reframe his ‘career transition’ to become a ‘research project’. Researching requires both patience and resilience. Research shows that 51% of executive candidates had been looking for a new role for four months or longer, with 1 in 10 still looking after 12 months. For 42%, they had been looking for much longer than expected.

The identity transition process helps executives to rebuild their sense of self beyond professional titles and roles. This systematic approach recognizes that career transitions happen more than once in today’s world. We need strong foundations that support professional success rather than depending on it.

As part of Declan’s research, he could see much consolidation and industry convergence was happening. New smaller, more dynamic, fast growth organizations were beginning to make bold steps into the marketplace. He started reading broadly about manufacturing innovation, not just for job search purposes but because he genuinely enjoyed learning about industry developments. “The transition was taking time but he was building firmer foundations,” his coach observed. “As Declan became more comfortable sharing his career story, we also helped him create his future ready pitch. This was crafted in alignment with what was important to him at this life stage, not just external expectations.”

His coach introduced Declan to the book “The Top 5 Regrets of the Dying” by Bronnie Ware. In her book, Bronnie shared her research from speaking to people at end of life. These were their top five regrets:

- “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

- “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.”

- “I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings.”

- “I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.”

- “I wish that I had let myself be happier.”

The first one really resonated with Declan—he now had the courage to live a life true to himself, not the life others expected of him. The identity work greatly improved Declan’s job search effectiveness. Instead of desperately seeking any role to restore his identity, he could evaluate opportunities based on fit with his values, interests, and goals rather than just title restoration.

“Once I understood who I was beyond my job title, I could articulate what I wanted from my next role more clearly,” Declan explains. “I wasn’t just looking for another multinational Ops role. I was looking for an opportunity to apply my problem-solving abilities and passion for people development in a culture that matched my values.”

Eight months after beginning his outplacement programme, Declan was appointed into a senior role for a growing renewable energy business. While technically a step down in title from Director, the role offered opportunities to build new systems, develop teams, and contribute to sustainable energy development—all areas that aligned with his rediscovered sense of purpose.

“The role is perfect for who I am, not just what I’ve done,” Declan reflects. “I’m not trying to recreate what I did in the past, I’m applying my capabilities in an environment that energizes me again. I know now that career success is as much about alignment with my values rather than just professional achievement.”

More importantly, Declan’s broader identity foundation means he’s no longer vulnerable to complete identity collapse if his professional situation changes again. “I know who I am now beyond my job title,” he explains. “My work is important to me, but it’s an expression of who I am rather than the definition of who I am.”

————————————————————————————————————————

John Fitzgerald is founder of Harmonics, an executive outplacement firm | www.harmonics.ie